| ||

|

> Research | > Conscience |

| ||

|

> Research | > Conscience |

What is the difference between good and evil, and how does one know?

That's a pretty important question, and it is one that many people have tried to answer over the millennia. People would like it to be stated as a single sentence, so that it's easy to understand. It turns out that a single-sentence answer can be given as an approximation. Beyond that, a few "rules of thumb" can be defined, which are adequate for decisions in simple situations. One can use a method of progressive elaboration to explain morality, and to make moral decisions in complex circumstances. So let's begin...

People tend to have a similar but vague concept of what is good, and they come by that concept naturally. Each person begins life as a baby, and as the child grows up, the child experiences being treated kindly by some people and less kindly (or even cruelly) by others. The child chooses people as role models, identifying desirable traits from his (or her) parents, teachers, friends, fictional heroes, etc. The child develops ideals for him or herself, and for the preferred behavior of his or her family, community, nation, and universe.

Moreover, there is evidence that shows that human infants have a tendency toward altruism. They derive joy from the happiness of others around them, and that they desire to help others who are in distress. For example, if a baby is near another baby who is crying, this often distresses the first baby, as evidenced by a sad expression or beginning to cry himself. Various studies of childhood development show that children will try to console another child, for example by offering a toy or a hug. Children get into squabbles too, and it is part of the growing-up process to learn how to resolve conflicts and reach happy outcomes.

The child also learns lots of rules! Societies have laws that fill many volumes of books, and those are just a subset of the society's ethical standards. (Typically laws are limited to what is practical and necessary to enforce.) There are also informal standards, from minor details such as how to properly greet another person to more significant standards around fairness, honesty, etc.

I recently had someone in my family taking driving lessons, and I was impressed by the fact that this activity includes many hundreds of rules, including memorization of road symbols, recommended driving practices, etc. More will be said about this later (because the "rules of the road" serve as a good example for some case studies) but my point right now is that there are a lot of rules in our world!

The child learns these rules the same way the child learns a language: one little bit at a time, at random! By the time a child reaches adulthood, they will likely have learned somewhere between 20,000 and 50,000 words. But if you ask a person to recite all the words they have learned in alphabetical order, they can't do it! The words come to mind only as they are needed, because that's the way the mind works.

Similarly, a person learns the rules without even trying. As the person learns each rule, he (or she) evaluates the rule against his ideals as they existed in his mind at the time. Any given rule will tend to produce particular kinds of results, and sometimes there are unwanted side effects. So the child may also modify some of the rules within his mind a he or she adopts them. And, as with the words, the person is unable to recite all of the ideals and rules that reside in his mind.

It is also typical of a person to believe that nobody taught him these things: neither how to speak nor how to behave. But that is not quite accurate.

Often a child's parents wish for the child to adopt behaviors that the parents consider to be "praiseworthy". Parents influence the child in various ways. Very small children such as babies and toddlers like to explore: they touch everything, put things in their mouth, etc. Because they could harm themselves by such exploration, the parents will stop their child from experiences that have severe harmful consequences. If a young child persists in attempting harmful activities, the parent may substitute less severe consequences so that the child will learn. Furthermore, as the child learns to communicate, the parents will explain things to their child and encourage behaviors that bring joy to their family. And they will serve as a role model for the child.

A person emerging from this process will often believe that he (or she) is a good person. Sometimes there may be occassions when he regrets what he has done, and at such times he may feel that he has fallen short of his own ideals. But it is typical that a person believes that he understands the difference between good and evil, even if he cannot explain the difference very clearly. This is sometimes described as "having a conscience."

Sometimes this self-assessment is one that other people round-about will readily agree with. But sometimes it is not! We see in the world a variety of behaviors emerging among people, and also there are differences among nations. In some nations people live peacefully, with widespread cooperation and prosperity, while other nations live in a perpetual state of civil war with widespread poverty.

Clearly, there must be differences in what children learn in some parts of the world as compared to others, which accounts for these alternate outcomes. And so, it would be useful to identify what is that knowledge that is missing, so that we can be sure to teach it to our children in our parenting, communication, and as a role model! And in particular, we might ask what is the basic foundation of this knowledge, that we might understand intuitively but be unable to explain! And how shall we determine that?

Ethics is often described as a set of rules that govern behavior. It turns out that there is a natural tendency for people to develop rules for interactions between them. The rules serve to regulate behavior, so that interactions will cause outcomes that are pleasing to the participants.

As an example of this, I will return to the rules of driving a car. Let us consider the fact that people do not wish to have collisions because of the cost and personal injury that can result. Let us go back in time, to the era when vehicles were first invented, and there were no rules. On the first primitive roads, we can imagine people being frustrated by the risk of collision whenever they approach another vehicle! To avoid collision, drivers may swerve either to the left or right side of the road. But to which side should each vehicle go? If one driver chooses his right while the other chooses his left, they are headed for a crash! Maybe they can stop in time if each stomps on their brake. But that is also a frustrating situation, because it means that they only dare approach each other at a low speed. This would slow travel, especially in busy areas.

So what might they do about it? One solution would be for each driver to stay on his right as they approach. Another solution would be for each driver to stay on his left as they approach. But which shall it be? How shall they know which is the "good" choice?

To make that choice, the citizens might rely on a ruler of the land. But how shall they be satisfied that the ruler makes the "good" choice? Is he not just another person, the same as them? So how is he to know any better than they do?

In an attempt to reach a resolution, the citizens might resort to a scientific investigation, because science is known to be objective. But will that solve it?

A scientific approach may be used to describe nature and predict outcomes. However, we need to reach a decision, so we are looking for something more than that. We are looking for 3 steps:

The description part of this case study is easy, because I have described it already. We observe the roads and notice that occasionally vehicles approach each other on the roads.

The scientist also seeks to use observation and experimentation to discover how nature functions. When he has a clear and correct understanding, he can make prediction of outcomes that arise from various conditions. So it becomes predictable in the early part of this scenario that vehicles will occasionally collide or almost collide.

Given a knowledge of human psychology, it is easy to predict that the drivers will not be satisfied with this situation. However, what follows after that is not entirely predictable...

It turns out, that some parts of nature have a random element. And it is also known that some phenomenon will follow a "random walk" in which order emerges out of disorder. This is one of those situations.

On this web site, there is a simple computer simulation of the drivers' choices. In the simulation, each driver interacts with others at random, and each makes a random decision about whether to take the right or left side of the road. Each driver also remembers the result of the previous encounter, and makes future choices based on the successes and failures he (or she) has encountered.

You might suppose that these random interactions go on forever, but that is not what happens. Eventually all the drivers end up choosing one side or the other. Either they will all choose the right hand side or they will all choose the left hand side. It is not possible to predict which rule will emerge, but one surely will. They don't actually require a leader to choose for them, because the rule will emerge regardless. (However, if the people did trust a leader to choose it for them, it would speed up the process.)

So which is the "good" choice: right or left? It doesn't matter to the drivers, as long as they all choose the same rule! Either way they achieve an outcome that they are all happy with. They would say that there is more than one good alternative, and they have chosen one of them.

This is typical of ethics. Often there is more than one right answer. But there is also definitely a difference between right answers and wrong answers! In practice, ethics is a combination of science and invention. Once a standard emerges, it is generally preferable to the individuals in the society to conform to the standard until such time as a better standard is invented.

Over time, rules are refined and elaborated. For example, the "right hand" vs "left hand" rule doesn't explain what the driver should do if he needs to pass through an intersection, or enter a driveway on the opposite side of the road. Entering the driveway requires an exception to the initial rule, and avoiding collisions at the intersection requires new rules.

We can see in the timeline of historical progress that there has been significant improvement over history. The people and societies who make use of the inventions in ethics have greater capabilities today and happier lives than any societies of the past.

Studying history is one method to use in the science part of ethics. Another method is the use of simulations, such as the NewWorld simulation that models behaviors such as cheating, warring, peacemaking, generosity, and responsibility of parents for their offspring (or the lack thereof). From these methods, the consequences of various behaviors can be identified. And this brings us to the last step, in which people invent and choose rules for producing desirable outcomes.

As shown in the timeline, progress in ethics has been very slow, occurring over millennia. People tend to hold onto traditions and conform to rules, without necessarily understanding how those traditions and rules have arisen. However, today we have widespread education and better knowledge of the social sciences than ever before. So there is the opportunity to accelerate progress, to produce a world, community, family, and self where each person can benefit from cooperation and the heritage of knowledge given to them. There is the opportunity for each person to be happier than ever before in the history of the world.

Thus far I have described ethics as a process in which people gradually invent rules. The people are guided by their own motives, and as they satisfy their motives that produces happiness among them. Each person chooses for himself what rules he shall follow, and by so doing the person casts a vote for the kind of world, community, and family he wishes to have.

However, a problem arises if a person follows rules slavishly, because no set of rules is ever complete. There are virtually always situations that the rules don't handle well, where there is an unintended side effect of a rule.

To continue with our "rules of the road" case study, let's use an example where a car is parked at a red light on a mountainside road. The rule says to wait until the light turns green. However, the driver notices some rocks bouncing off the mountainside above him and he observes that there are no other cars in or near the intersection. The drivers' rule book does not offer any exemption for falling rocks, because the rule makers never thought of that. Fearing that he and his passengers would be caught in a rock slide, he breaks the rule and drives through the intersection to escape.

Do you suppose he is evil because he broke a rule? Or is he a hero? Did he do a good thing?

Most of us would realize that his behavior was in conformance with the PURPOSE of the rule, which was to avoid damage and injury. So he was following a higher rule.

To deal with deficiencies in formal rules, societies institute political systems for changing rules. They also often define a higher level rule set, such as a constitution, which are less specific but which override the more detailed rules.

Throughout the ages, philosophers and religious leaders have tried to determine which is the highest rule, which would override all others. It would be very handy if this could be stated in a single sentence, so that it would be easy for everyone to learn. There is some merit in this approach, but it has its own problems--not the least of which is writing the sentence! However, it could be useful as an approximation...

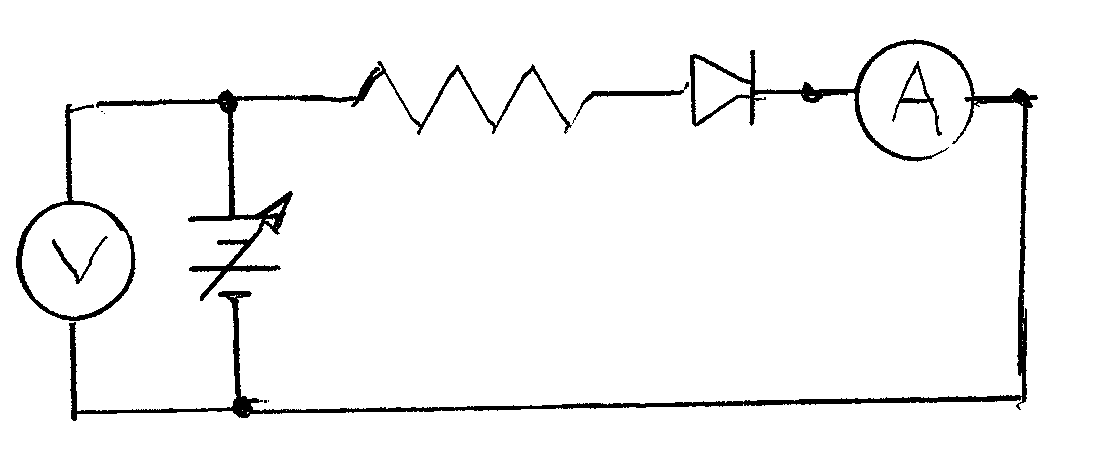

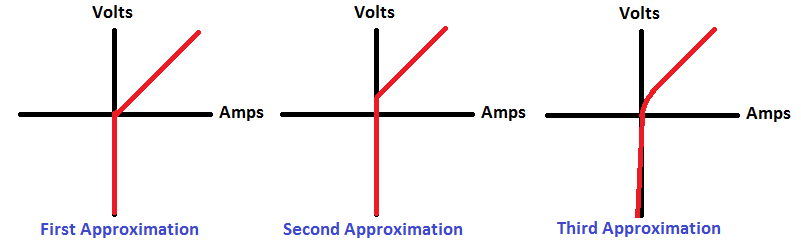

Approximations can be useful in science, engineering and ethics. As one example from my past (when I studied electronics technology), here are three approximations for the current through a circuit containing a diode:

|

Diode circuit. If a diode was perfect, current would flow when when any positive voltage is applied but not when a negative voltage is applied. However, a real device needs some minimum voltage applied before it turns on, and it doesn't turn on instantly. It may also leak some current in the reverse direction. |

|

| Theoretical current flow measured at the ammeter "A" when voltage is varied and measured at the voltmeter "V" |

Now let's suppose that an engineer is designing a circuit that contains hundreds of resistors, diodes, transistors, and other components. He needs to be able to determine what the voltage and current will be at any point in the device. As it turns out, this is fairly easy to calculate with the first or second approximations, but difficult to do using the third approximation. For most practical purposes, the first and second approximations are close enough!

As another example, consider Newton's laws of Physics as compared to Einstein's laws. Einstein's rules are more accurate, but most people still use Newton's laws for every-day kinds of calculations. Why? Because for objects moving at low speeds, that we typically encounter in daily life, calculations based on Newton's rules are sufficiently accurate, and the calculations are much easier!

Approximations are also useful for ethical rules. However, in order to explain how we might use approximations, first we need to back up a little bit and take another look at human behavior...

At the outset of this article I explained how each person develops ideals beginning in their childhood. These ideals together form a picture of what that person wishes his world, community, family, and self would be. His actions serve as votes to bring those things into reality. Also, the child discovers that his own vote alone is not enough, and that he needs other people to vote for the same things.

How is the person to encourage others to "vote" in the ways that he would like? There are typically one of two approaches that may be used: one is to use force or the threat of force, and the other is to offer a benefit to the other person. As an example of the latter, one person may choose to be kind to another person in expectation that the other person will be kind to them in return.

These same methods can be found among various species in the animal kingdom. Some animals have altruistic behavior, but some exhibit cruel behavior. For example, adult male bears and gorillas in some cases will kill their own children. This seems counterproductive to the survival of the species, but the problem is mitigated by the fact that the mothers protect their children. Some animals have evolved to the point where they can join groups and coordinate their activity, but typically that is limited to a small group, such as a pack of wolves, troupe of gorillas, or herd of cattle.

Humans have developed the capability to form groups of unlimited size known ans "societies" or "nations." Like simpler animals, humans can choose aggressive or cooperative behavior. Groups of any size can be created to overcome an oppressor, and sometimes that group itself becomes an oppressor. A computer simulation, "NewWorld" models various kinds of animal and human behavior. In this simulation, the struggle for dominance is modeled by the "Warrior" behavior type.

However, there is a disadvantage of warrior behavior. I won't get into all the details here, but there is a cost to the species for the dominant group to maintain control, and there tends to be widespread misery among the non-dominant group(s).

Alternate behavior type in the simulation are the Peacemaker and Generous Peacemaker. Peacemaker groups do not rely on force to gain cooperation. The animals have solidarity among themselves because they have empathy among them. This results in altruistic behavior. Unlike the warriors, the Peacemakers do not divide into competing groups of oppressor and oppressed. If all other conditions are equal, the Peacemakers will tend to gain dominance over the warriors and over the ecology as a whole, and happiness among the people becomes more widespread.

I would suggest that as early human civilizations arose, thousands of years ago, their cooperative capacity was limited and Warrior behavior was more common than Peacemaker behavior. Warrior behavior still occurs in some parts of the world, where wars are rampant and widespread suffering tends to build anger, fear, and distrust that overwhelm the people's normal tendencies toward altruism. However, in much of the world there is peace and people seek to promote each other's mutual well-being.

Humans have developed incredible knowledge and capabilities compared to past times, which includes the capability to totally destroy our own planet. It is no longer acceptable to continue fighting for dominance in the way that our ancestors might have done, and that some primitive animals might still do. For the survival of our own people and our planet, we need to expand cooperation to a point where it is universal among all who have the capability to cooperate.

That means that individual people need to learn how to cooperate. This is important not just for the future of the world, but for the happiness of individuals. Think about it: would you personally like to have the rules and coordination of activities in your society, community, or family done the way the primitive humans may have done it long ago -- as a struggle for dominance? Or do your ideals involve making decisions via the use of reason and the desire for mutual benefit? I'll assume it's the latter, so now the question is: how can you sum it up in the fewest number of words possible?

As explained at the outset of this article, people tend to adopt rules for their mutual benefit, but rules have a weakness that they cannot cover all situations satisfactorily. One way to solve that is to set an overall goal that is easy for people to understand and that they are likely to agree with.

When we begin to understand how the mind works, we see that it is a learning system that is guided by built-in motivators. The satisfaction of the motivators results in happiness. So we can sum that up by saying that each person seeks happiness. We have also seen how altruism has arisen in the natural world and among humans; it is part of a human's motivational system. Via computer simulation we can see that altruism is important to group solidarity and cooperation.

Barring environmental influences that interfere with normal development, it is normal for a human to care about other people, and often the person will also have empathy with some other kinds of animals. Therefore he seeks happiness for others too. When others feel the same way, this results in cooperative relationships.

Together people develop rules of interaction so that their interactions produce mutually desirable results, as in the "rules of the road" case study I presented above. When one of their rules seems to have an undesirable side effect, they resolve it by focusing on a higher goal.

How can this goal be stated? Here is the shortest phrase that I have ever seen that conveys the idea:

SPREAD HAPPINESS!

Notice that this phrase does not replace all other rules. When travelling down a road, people still need to have a standard for which side to drive on. And many other rules are needed too. But when an unusual situation arises in which rule-following is counterproductive to mutual happiness, this overarching goal serves as permission to override the rule.

The first approximation is short but also it is a bit vague. One wishes to "spread happiness", but how much is to be spread and how much is to be just kept to oneself? In order to be a bit more precise, let's move from a 2-word phrase to a single sentence:

"Do unto others as you would have others do unto you."

This is one way to state the Golden Rule. It is a concept found in many societies from ancient times to today, though often stated in somewhat different words.

The assumption here is that each person wants to be happy, and in any interaction with another person they will seek to make that person just as happy as they themselves would wish to be.

So, for example, suppose you are headed off to see your favorite movie at a theatre and you notice that your neighbor's car is stuck in the snow. You could stop to help him push it out, but then you would be late for your movie. So what do you do?

According to this rule, you imagine yourself in his position. That effectively means that you treat his wishes as equally important to your own. If it would be more important to you to have your car pushed out of the snow than to see the movie, then you help push him out; otherwise you would go to the movie.

This is more precise than the 2-word slogan because it gives guidance not just to spread happiness, but defines the extent to which you would do it an an interaction with any other person.

However, the phrase still lacks precisions about how to handle some situations. Suppose for example that it's your friend's birthday. You love music and plan to give him some music recordings as a gift, but he doesn't like music much--he likes art so he would much prefer to have some paints. Would giving him music be "treating him as you wish to be treated?" From the sentence alone one might think so, but if one examines an elaborated version of the rule, then one would give him what he wants.

So we see that this rule is pretty helpful, but it does need a bit more explanation beyond just the sentence itself. That is why I call it an "approximation."

"Optimizing happiness" across a group is sometimes referred to as "utility theory." The term "utility" means the usefulness of something, or the satisfaction that one can get from it. Utility theory is an economic theory that arose in the era of the industrial revolution, based on the idea that the economy should be designed to maximize the aggregate satisfaction of the population. In other words, the goal is to maximize happiness.

One of the major features of this concept is that each person is equal. Prior to this time, the aristocracy generally considered themselves to be superior. Therefore they believed it was justified to tax the peasantry to the verge of starvation in order to build magnificent palaces for themselves. The peasants often accepted this claim. Only the aristocrats were educated, so they seemed to be smarter. But eventually it was discovered that anybody could be taught to read. Moreover, following the invention of Gutenberg's printing press in the 1400s, books began to be widely available. By the 1800s, a large part of the population in industrialized nations had achieved the ability to read. Knowledge became available to anybody, and the illusion was broken.

Like the Golden Rule, the goal of Utility theory is to increase happiness. But the Golden rule only deals with an interaction between one person and any other; it isn't very precise for handling decisions where a lot of people are affected at once.

For example, suppose that the staff at a factory are conferring about the idea of introducing a new process that has an undesirable side effect: it pours pollution into the surrounding farmland, making it unsuitable for farming. Let's further assume that there are 10 farmers affected and 20 factory workers, each of whom are earning the same salary each year. From the sale of the new product, the salary of the factory workers would be tripled. In utility theory, money is often treated as a surrogate for happiness. So, at first glance it would seem to be reasonable to proceed with the project (because the happiness of 20 workers exceeds the misery of 10 farmers).

However, in utility theory it is also recognized that the joy one gets from any commodity declines as more of it is received. That's called "declining marginal utility". Adding one or dollar to a worker's salary adds more joy than adding the second $1, and each subsequent dollar contributes less happiness than the previous one.

If we take this into account, we can realize that the farmers losing all their income would have a much greater impact to their happiness than the salary increase for the factory workers would be to theirs. We must also remember that each person is to be treated as equal to each other person. Therefore, a better way to solve the problem would be to compensate the farmers using factory money, giving them double their former income. This would still leave enough money to double the income of the factory workers.

That sounds like a reasonable solution, but there are some potential flaws. Utility theory does not consider anyone apart from the adults involved at the time. What if animals had used that farmland too? They are not considered. Will the land be polluted only while the factory is in use, or for generations afterward? The interests of future generations are not considered. They cannot be counted in the calculation because there could be an unknown, perhaps infinite number of people affected over eternity.

Utility theory is useful if only adult humans are affected and they are all pretty much identical. But if they are not, then further difficulties arise. Consider, for example, a bully in a school yard who takes intense delight in tormenting a weaker student. The schoolyard supervisor approaches the bully about his behavior, but he defends himself with this argument: The fiendish delight he gets from tormenting the other child has much greater magnitude of happiness for him than the relatively mild discomfort that the other child suffers. Therefore his happiness outweighs the other child's unhappiness.

What do you think of that argument? Think of your own ideals that you have developed over your lifetime. How do you want the world to be? Would you like a world in which you might be subject to torment merely because some other person takes joy in it? Or would you want action taken to discourage that kind of behavior wherever it would occur? Perhaps there are some kinds of motivators that don't deserve to be satisfied!

In order to address the limitations of utility theory, some further refinements are required. These refinements are consistent with the fundamental approximations, because they produce a world that practically anybody would prefer if they think beyond their immediate self and surrounding people. Taking a very wide view, a refined solution will handle not only far-away nations, but also the people of the future. It will also consider that we care about animals too, beyond just humans.

We cannot measure the happiness of an infinite population, which would be required for "optimizing happiness." However, we can assign some kinds of rights to an infinite population.

There are two kinds of rights: rights of prohibition and rights of obligation. The first prohibits people from carrying out particular activities, and the second obligates them to carry out particular activities. It is simple to apply rights of prohibition to an infinite population: one simply commits to not harming other people, now or in the future.

For rights involving obligations (to require that one person should help another, such as to provide education for children or other defined benefits), it is not possible for a small population to handle the burden of providing the benefits to a large, unlimited size group. However, a group can set obligations to optimize happiness within the group. Then from its surplus resources it can use the expanding wave of generosity to expand the progress of happiness outside of the group.

In a similar manner, one can define rights for animals and the ecology, in order to avoid causing suffering, and to preserve the ecology for the future.

So, we end up with a combination of a rights-based approach to morality and a happiness-optimization approach, which are basically two methods of spreading happiness. Some philosophers might debate which method is best, but they are not mutually exclusive. This has not been well understood in the past, but now we can see why there were different approaches, and combine them in a unified theory.

Similarly within the concept of "optimizing happiness within a group" we can apply refinements. Cruelty is not necessary for happiness even in a person who may have a cruel streak in their nature, so we simply don't count it as a "joy" to be counted as if it were a benefit to a society.

Another refinement is the handling of death. It could be noted that after a person is dead, they have no joy nor misery to be calculated into an overall happiness score for a society. But death is an unwanted condition. There is an opportunity cost for the missed years of joy that the dead person could have had, in cases where they died prematurely due to situations such as murder, preventable disease, etc. This cost is a negative value applied against the overall success core of a society.

One can determine an optimum course of action, or at least a range of acceptable actions, using a "fourth approximation" that has these refinements, among others. The Pathways methodology is designed to do that, supported by software that will track rights and calculate happiness estimates for a group, the Pathways Planner.

We can see that increasingly sophisticated methods can be used to handle a complex circumstances, but also that simple methods are also very practical to guide moral decision making in many situations.

At the outset of this article I explained how people develop their ideals. From the life experiences as each person grows up, he develops his own concept of how he wishes the world would be, as well as his community, his family, and himself. It is kind of like painting a picture, but more like a large mural. There is no limit to how complex he can make it.

In so doing, he can overcome all of the limitations of simplified "approximations" such as those I have presented above. If he doesn't think that "fiendish delight" should be rewarded in his ideal world, he can design his ideal accordingly. If he thinks that some animals should be treated kindly in his ideal, he can include them -- notwithstanding that some simplified theory might not. If he cares about future generations and wants the world to continue on indefinitely, generation after generation without end, he can include that too.

If each person develops their ideals indepedently, there will be some differences between those ideals but there will also be many similarities. That's because there are certain essential motivators that each living person must have, and people will design their ideals so that their motivators would be satisfied.

So, for example, if you compare independently developed ideals, you will see that there are typical things that arise in all of them. People will typically wish to have abundance instead of poverty and starvation. They will wish to have peace instead of war. They will wish to have health instead of sickness, etc.

Each action that a person undertakes isn't just a choice for themselves, but it is a vote for the kind of world they want. As a simple example, throwing trash out of a car window as one drives down a highway isn't just a means of getting rid of some trash: it is a vote for a trashy highway. Disposing of the trash that way may be fine from a self-interest point of view, but that is very short-sighted. It fails to consider the voting effect.

This is illustrated very clearly in the Story of the Devious Politician.Happiness is achieved through the fulfilment of motivators, but there is more than one way to fulfil a motivator. As a simple example, a person may want to stay up late at night to do something that they want, but that is simultaneously counterproductive to getting enough sleep. So, rather than simply being carried along with the desire of the moment, people seek for ideal solutions. An ideal solution is one that satisfies the desires but without unwanted consequences. So, for this example, the person might do their desired activity in the day and sleep in the night.

By defining shared ideals, we can develop strategies that are more specific than simply "do what you want." They result in us getting what we want, but in a more prescribed way than simply drifting around according to the emotion of the moment, and with more satisfaction overall.

Ideals define the direction we want to go, but not necessarily the exact speed we want to take to get there. The specific speed is a value judgement. Sometimes people need to reach agreement on a value judgement, but it is not always necessary. Sometimes the most practical solution is for people to act indendantly, each applying their own values. In those cases, agreement on the direction is sufficient.

In fact, difference in opinion on values can sometimes be advantageous. In any given society, there is a need for people to undertake different roles. If one person chooses to be a doctor because they feel the need for better medicine is the most important, while meanwhile someone else chooses to be an educator, and someone else chooses to be a researcher, etc., that's all fine! By contrast, if the rules of a society were so specific and rigid that they dictated everything each person is to do, and if those same rules applied to everyone, then there would be no means of accommodating different roles and developing different skills. So allowing some degree of individual discretion within decisions is also part of the ideal world!

The ideals could be stated as an approximation, or the ideals could be elaborated to any level of detail. However, as the level of detail is increased, people will tend to find fault with some of the details. Ideals seem to be most practical when they are kept fairly general.

As an experiment to test a few basic "shared ideals," I developed an Ideals Survey that is posted on this web site. A few people have responded, indicating that most agree with these ideals. You are welcome to respond to it too!

If ideals are discussed within a group, it often serves to solve problems in which people take oposing positions. For example, if a group is making a decision about some project, it is helpful to discuss the ideal results for that project. If the real outcome must fall short because of limitations in resources or some other such reason, at least those will be explicit decisions. Often I find in this world that people shoot for "second best" in their undertakings without recognizing when "first best" is possible.

An essential element of Ethics is cooperation. If a person lived alone on a tropical island, he wouldn't have to worry about how his decisions affect others nor vice versa. But that would be a very limited, primitive life. So each of us seek instead to interact with others, and that involves convincing them to behave in ways that we like. Convincing is done using words, rules, and by demonstrating to others that we are trustworthy in meeting our commitment to the ethical behavior we have agreed upon.

Using these high level ethical goals can be very helpful for reaching agreement. The golden rule, for example, is very popular across many civilizations. Some applications include:

The golden rule in particular has the advantage that most people know it already, and therefore no explanation is required. There are lots of circumstances where it is quite adequate for reaching a resolution of the problem. It is only if the problem goes beyond what the Golden Rule is meant to solve that you would need to drop to a more complex approximation.

There are various other "rules of thumb" that have been developed over the course of history in order to separate the "good" alternatives from the "evil" ones. You can use any of these much the same as you might use the first or second approximations above.

One example is a basic rule that prohibits dishonesty. Whenever any person does any action that they are ashamed of, they typically lie about it. So if a person uses as a test whether they would be willing to tell the truth about something they do, they will only choose activities that they would be proud of.

Various authors have come up with different tests or criteria for identifying the behaviors that they recommend. One may be tempted to "throw up their hands" and conclude that no sense can be made of all this confusion. But there is another way one can use these criteria: as a filter. If you are proposing a particular course of action, and you test it against the "definition of good" as given by ten different authors who have each made a sincere attempt to define it, and it passes as "good" in all of the definitions, then it's probably O.K.!

One particular example of that is the "Four Way Test" adopted by the Rotary organization, which uses four criteria as a filter for ethical behavior.

As I mentioned earlier, ethics is a combination of science and invention. In science there can be new discoveries, and inventions can be improved upon. Usually people have no difficulty to identify the gaps between how they wish their world, their nation, their community, their family, and themselves would be, as compared to how they actually are. If people focus their attention on making things better, they can often find a way. That includes both making the desired improvements through joint action, and also improving their understanding of how to cooperate effectively together.

What do you think of the content on this web page?

| Site Search | |

Return to Universal Ethics home page |