| ||

|

> Research | > Standards |

| ||

|

> Research | > Standards |

Any society will inevitably define standards of behavior. Standards are adopted so that interactions between members of the society will produce pleasing results rather than displeasing ones. This is a natural process that is described in the Rules of the Road Simulation. Over generations, the rules are refined, which is an important part of Social Progress.

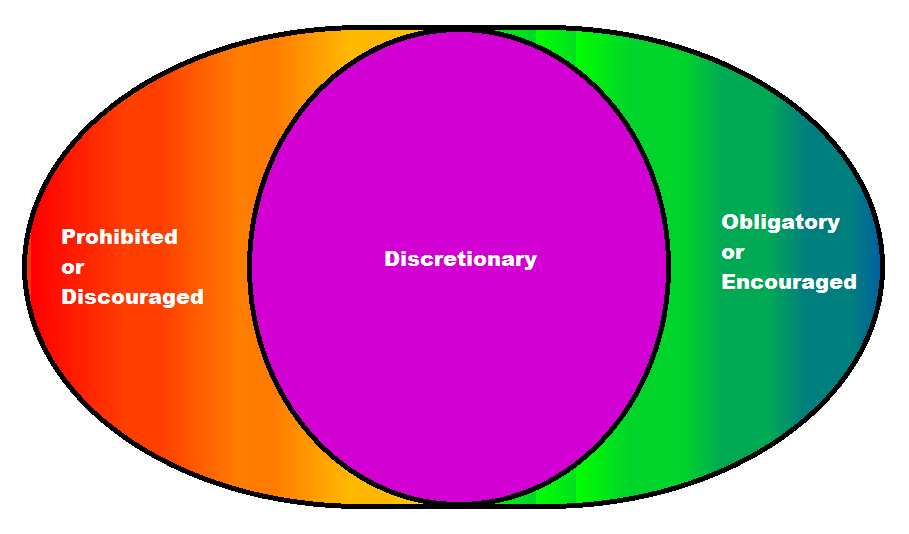

We can look at standards from a scientific viewpoint, which is to observe them, describe them, explain them, and predict the emergence of new standards. Of greater interest, however, is to engineer new and more satisfactory standards. The intent is to obtain desirable results for modern and future societies more quickly than via a trial-and-error evolutionary process. So, let's look some models of behavioral standards...

In a very simplistic concept, every action could be classified into one of two groups, moral and immoral. Suppose that one made a long list of moral and immoral behaviors. For each immoral behavior, let's draw a black dot on a green background. For each moral behavior, let's draw a white dot. If we squeeze all the dots together, we might get something that looks like this:

| Illustration representing the "black and white" concept of morality. |

However, that concept is a bit weak, because among the immoral actions there are some that are worse than others, and also among the moral activities there are some that are more praiseworthy than others. There is a difference between a person who is very generous, and one who is not; we would very much prefer to be surrounded by the former, so it is not sufficient to merely classify all of them as "good."

Moreover, there are some activities that are neither good nor evil, but simply a matter of personal preference. For example, if a person likes to eat fruit and is trying to decide whether to eat an apple today and an orange tomorrow, or vice versa, it really doesn't make any difference!

As in the Rules of the Road Simulation, the behavioral rule that emerges (passing on the designated side) constrains behavior but does not dictate it. In that simulation, inspired by the Bumper Cars Online Game, the drivers still have choices of destination. Whether they choose to go to the shopping center now, or to work, or to other destinations, is left up to them. That's because their individual desires vary over time, and therefore they are happier to have those liberties than to be restricted to rules so rigid as to dictate every action. The "black and white" model doesn't accommodate that because it has only prohibited (evil) and mandatory (good) categories of behavior, but nothing discretionary.

To overcome those weaknesses, we need to have an improved concept...

In this diagram, each behavior is a pixel that represents behavior in one of three areas. There are so many behaviors that they appear as solid colouring.

Totally separating the red and green regions may seem like an oversimplification, because there are some actions that produce benefits but also involve displeasure. However, there will be a balance of how the affected person(s) are affected overall, and whether they prefer to incur the outcome or prevent it.

It is also important to note that there are an infinite number of good things that a person could potentially do to help others, but no one individual will have the time or skill to do all of them in his (or her) lifetime. So it is not possible to make every good thing obligatory for every person.

That is why, on the right-hand region, not every item is a mandatory action for each person. It is a range of mandatory and encouraged outcomes. Each dot carries a condition with it, that defines what conditions make it mandatory, the strength of the obligation, and the roles for which it applies.

To explore this further, let's use an example. Consider a person who wishes to have surgery to fix a medical problem, such as a broken leg, damaged knee, hernia, etc. Although the surgery itself will be done under anesthesia, inevitably there will be a recovery period in which the person will feel some pain in the affected area. So it is a mix of desirable and undesirable outcomes for the patient.

Let us assume that the person understands the consequences of the choice very well, and determines that the benefit of the surgery far outweighs the suffering involved. If he could solve the problem by himself, it might be a straight-forward discretionary choice. But he cannot perform the surgery on himself!

If someone else must perform the surgery in order to have the desirable outcome, the disabled individual would very much like to live in a society that places an obligation on someone else to do it! That means that the society must have some rule of obligation that we would represent within the diagram as a dot within the green region.

That obligation could be assigned to anybody who knows how to do the surgery (a surgeon). However, typically there aren't many surgeons because it is a skill that is time-consuming to learn, and it would be a heavy burden on surgeons to require them to apply their skill in all such cases without compensation. Perhaps the patient himself could pay for it, but what if the patient is a child, or a student or any other person who has not accumulated enough money to compensate the surgeon?

So, in that situation, the patient relies on a number of good people to pay the cost and split that cost among them. In a very well organized modern society, those good people are pretty much the entire population of citizens, so the money is collected from all who have surplus resources to contribute and it is dispensed in an organized manner.

Societies organize themselves via their governments that pass and enforce laws, so let's consider the legal standards that nations set for the behavior of their citizens...

Whenever people interact, there are the possibilities of those interactions resulting in a) synergy in which both benefit, or b) a situation where one causes suffering to the other, or c) where both suffer. So, it is natural and inevitable that the people in the society will develop rules governing the interactions in order to produce the kinds of results that they want.

Sometimes there is more than one way of achieving the same result. An example of this was given in the Rules of the Road Simulation, in which a "right-hand passing" or "left-hand passing" rule would emerge. Because there is more than one way of producing the same result, different cultures may adopt different rules. However, underlying the differing standard there is often a common goal to be achieved; it is that element that is universal across cultures. Over time, the people in societies tend to learn an to refine their standards to produce results that are more pleasing to the population overall.

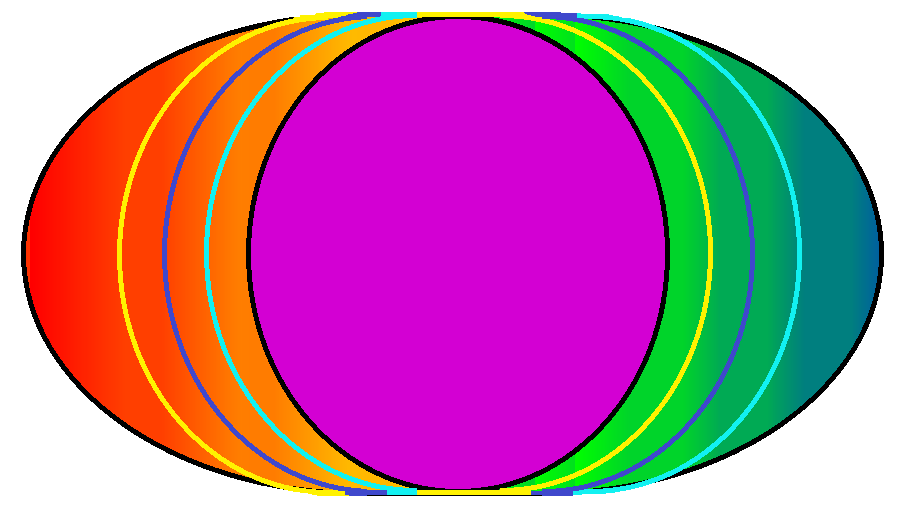

As people of the society learn the emerging standards and the benefit of them, they tend to conform to them voluntarily. But there are some who do not, and therefore a society will develop and enforce laws. The legal standard of a society is represented in the following diagram by yellow arcs in the left and right regions:

In this diagram, the areas of behavior regulated by laws is as follows:

Typically the moral standard commonly adopted by citizens of a society is more restrictive than the legal rules. The legal rules are more explicit, because they are written for use by citizens, lawyers, police, and judges. However, some things are simply impractical to enforce, and therefore they are not included in the prohibitions and obligations defined in the legal rules.

In the diagram below, a typical "moral standard" of a society is represented by the dark blue arcs in the diagram below. There are also light blue arcs (cyan colour) which we will get to in a moment.

You will notice that the dark blue arcs fall to the right of the legal standard. In the prohibition region all items to the left of the dark blue arc are morally prohibited, which is a wider range of prohibitions than the legal standard. In the obligations region, all items to the left of the dark blue arc are required, which is a wider range of obligations than in the legal standard.

Although the society's moral standard has no legal enforcement, people do encourage compliance with their moral standard by how they treat other people. Individuals give gifts and privileges to those who are deemed worthy and withhold them from those who are not.

In the preceding diagram there was also a light blue oval, to the right of the blue "society moral standard" described above. That's because there can be a "sub-culture" within a society that has a more restrictive standard.

Also there are standards that are adopted between friends, and within families, where members may expect a higher standard of kindness and generosity among them than they would find within the general population.

These standards are not all shown on the diagram, but additional arcs could be added to show them. They are not necessarily all the same shape, either, because different groups may separate out the behaviours differently and define their own "behavior scenarios" that make up the dots in the diagram.

Any given society's standards of ethics are not necessarily ideal. A standard is an invention, and any invention can be improved upon. There may be some severe harms done to some members of society that are permitted in the standard. There can also be benefits that are possible for the members of society that are not realized.

When there is progress in a society, generally that progress is manifest in a sub-group first, before it reaches the rest of society.

An example of this is slavery, that was long ago permitted in many societies, but gradually abolished across many generations. One of the most recent historical instances of that was in USA in the 1800s. The change occurred for all of society, but was preceded by some sub-groups who took action to free slaves, and who demanded the prohibition of slavery.

Typically the behavior of a society overall lags the best practices that have been discovered within the society. The "moral standard" of the overall society may be a bit backward, and that also affects the legal standard. This can result in some inconsistencies.

For example, in most nations one requires a prescription to buy medicines that have potentially harmful side-effects. However, exceptions are made for some drugs such as nicotine (in cigarettes and vapes), alcohol, and in some places--marijuana. Why? It's because enforcement is impractical. These drugs are mostly used for harmful non-medical purposes, for which no prescriptions would be offered. There are simply too many people addicted to them, who would be unwilling or unable to comply with a consistent law that included those drugs. In general, any law that requires more than about 10% of the population to change their habits is doomed to fail. The people need to voluntarily change their habits first.

If people wish to make wise decisions for themselves, that will bring the maximum benefits without adverse consequences, they should not assume that all common practices in the society are the best choices. A better strategy is to investigate the consequences of all manner of behaviors, in order to determine which to adopt. It is also useful to understand how the standards of societies arose, because many of the standards are useful, and one can benefit from those discoveries of the past.

You may notice that in all of the preceeding diagrams, the helpful behaviors in the rightmost area of the diagram (the blue area) are encouraged but are never obligatory. There is a reason for that: it's because there are always more good things that people can imagine to do than are possible for all the people in the society to actually do. So people have to make choices among them.

Apart from helping people in one's own nation, one can also do charitable acts to help people in other nations. Moreover, there is a need to develop technology and medical cures to help the people of the future. There are an infinite number of people who might exist outside of one's nation and in the future. So anything that one person could possibly do is only an infinitesimal contribution to an infinite need.

So, how does a person decide how much to contribute? One solution is to keep for one's self what is needed for self-maintenance (food, clothing, etc.) and to apply all or part of one's surplus capacity to doing good things.

This produces an effect that I call "the expanding wave of generosity." Not only does one's action help other people, by rescuing them from famine or disease, but it also enables them to help other people. So, generosity originating from one person spreads like the ripples from a pebble thrown into a pond:

|

Image borrowed from poem, I dropped a pebble in a pond |

But this leaves the question still unanswered about how much of one's surplus one should donate. One approach is to take a vow of "perpetual poverty" and give it all away, for the benefit of others. For example, one could give all one's time and money to scientific research that would benefit future generations. But consider the very next generation, who applies the same strategy, and lives in poverty for the benefit of the next generation after them. And the next generation also lives in poverty for the benefit of the following generation. And so on, forever, they all live in poverty.

I think you can see the flaw in that. There is some generosity that is too much.

There is also a flaw in no generosity at all. All of us benefit from the learning passed down to us, and for the food and support we received as children. We all want that to continue.

The problem is to determine an appropriate balance. That is a subjective matter, which brings us to the next point, about worthiness:

As I have illustrated in the standards diagram, there can be different standards of behaviour in a society that involve different levels of effort to help others in the "obligatory or encouraged" region. There can also be differences at the "prohibed and discouraged" end. The concept of "worthiness" is relevant to how people and animals are treated in both regions.

To explain this, we'll start at the blue/green end of the diagram. Here, the standards differ in the level and types of generosity that is prescribed.

Let's take a moment to think strategically about giving to help others. If you are donating time or money to help someone in trouble, which is more effective:

Alternative "a" makes use of the expanding wave of generosity, that could over time bring help to a large number of people, whereas alternative "b" helps only one person.

Clearly, the generous person is more "worthy" of your help than a selfish person.

Nevertheless, it's not always easy to differentiate when helping someone whether they will "pay it forward" or not. Sometimes it is necessary to take a chance, help them, and observe. Also, sometimes people can be "converted" by being helped, so that they become more generous than they were formerly. Recipients of help can also differ in their capacity to help other people afterward (and there can be a lag, such as when a child is helped--children can't do much to help others until they are older). It is up to the donor to look at the results, check for appreciation, and look at any other clues in order to make the best judgement that he can.

Worthiness is also relevant when choosing friends, and especially when seeking someone to be a mate. Like most of us, you would probably prefer to have friends who are at least somewhat generous. If you are single and looking for a candidate to be your spouse, you would also prefer to have a generous companion that would do kind things for you.

Suppose, however, that you are not generous yourself. What are your chances of finding a friend or mate who would treat you with generosity? It's not very likely, because they would realize that would only be a "one-way street" of them giving and you receiving, so they would not agree to be your friend. When you understand the strategy of optimizing generosity, as I have explained above, you can understand why they would prefer to have different friends instead.

Moreover, in a close relationship like a marriage, a mismatch in generosity between partners can be a big problem even if the more generous one doesn't mind the stinginess of the other. That's because a generous person is generous in general, and not just to one particular recipient. Moreover, in a marriage partnership their money is shared, along with their other possessions. The generous partner will be giving a lot of time and money to charity, but the other partner would prefer that it is kept for themselves only. This difference in values could cause conflict between them.

There can also be differences in values in the red and yellow region (prohibed or discouraged behaviors). Society has prohitions to protect people from being harmed by others in the extreme red end of this region. There is an assumption that each person is deserving of this protection, sometimes called the "innocent until proven guilty" assumption. But if a person violates the rules by carrying out prohibited action, the society will protect itself by taking action to deter or prevent the individual from repeating the behavior.

In an extreme case, the offending indidual may be put into a cage (jail) so that he can't harm others. Notice that this takes away his liberty. Taking away a person's liberty is a prohibited behavior, and normally the society would not allow it. However, by committing the crime, the criminal has disqualified himself from the society's protection against loss of liberty. He has made himself unworthy.

In less severe cases (only discouraged but not prohibited) there may be differences in values in what is accepted. Sometimes friends may tease each other or treat each other roughly, and yet it apparently doesn't bother them; but in other cases friendships are destroyed by such treatment. Depending on their values, friendship can be a tough thing that can be tossed around like a football, or it can be a fragile thing like a crystal glass that shatters at the slightest disturbance.

When people are deciding the standards that should apply to their friendship or marriage, they need to consider the extent to which minor annoyances are acceptable to them. Generally they are hoping that in a close relationship a higher standard would be maintained than the legal standard or the standard expected of strangers. But it's a "two way street" and sometimes a person can't find a companion that meets that aspiration because of their own shortage of consideration for others. In other cases they think they have found it, only to be disillusioned later. It is often quite amazing in the case of disillusionment how the behavioral standard of the couple can degrade to a point where they treat each other worse than strangers.

Within a nation, it is necessary to set a minimum standard of behavior in both the red/yellow and blue/green regions.

On the blue/green end, it is necessary to set a minimum standard of generosity to avoid the problem of freeloaders. Also, there is a certain efficiency to collecting money via taxes and allocating it, as compared to the fundraising costs of independent charities. Moreover, people have an expectation of benefits that they want to be eligible for, and to be guaranteed to have those benefits if the need arises. There is a cost to that, and a level of taxation that is needed in order to support that guarantee.

Usually the national programs to help people are designed as a modest standard that still leaves a lot of discretionary-use money in citizens pockets. This allows people the freedom to make donations of time and money on top of the money spent via the government. That way the citizens can also have flexibility in the kinds of good things they wish to apply their resources to.

There can be a variety of standards within a nation, and in sub-cultures, and in smaller groups such as family and friends. These standards can have different levels of generosity, and in general that works as long as reciprocal relations are maintained. In other words, one would not expect to be the recipient of generosity of a greater level than one's own generosity.

On the red/yellow (prohibition) side, although there may be some cultural differences in how things are done, there will be standards that every nation will want in order to prevent harm to current and future people. There is also a rationale explained elsewhere on this site for offering some kinds of protection to animals and the ecology.

So, although there an be variations in behavioral standards in societies and within subcultures, the differences in these standards are not entirely random. There is a core that arises from inevitable essential needs that exist in any creature, such as the need for food, water, shelter, etc., and to not have those things arbitrarily taken away. Likewise there is natural synergy that gives power to people working together, with the strongest power to those who can cooperate on the largest scale--and most effective of all on a universal scale.

But there is also variation among people, in their desires of what they want and how much, and to accommodate that variation there has to be some flexibility in the standards that are developed. Hence in practice we see some common standards emerging over time, and accommodation for variations in standards among subcultures as the individuals decide what kind of environment they want and "vote" for it with their actions.

What do you think of the content on this web page?

| Site Search | |

Return to Universal Ethics home page |