| |||

|

> Skills | > Estimating Wellbeing | > In one person |

| |||

|

> Skills | > Estimating Wellbeing | > In one person |

To estimate the wellbeing of a person under particular conditions, we will judge if he (or she) would be happy in those conditions. Here are some ways to go about it.

The easiest way to estimate how happy a person would be, is to ask them. They imagine the scenario and it comes into their mind what it would feel like. This is not a precise way to measure, but often it is adequate. In the topic Pursuing Happiness a simple scale was proposed, represented by symbols similar to traffic lights:

The negative numbers represent undesirable results while the positive ones are desirable. People have various motivators that need to be satisfied, that comprise the components of happiness. Each of them can be rated separately, according to whether the scenario satisfies the motivator or does the opposite.

If there are multiple alternatives to choose from, the person reports how he will feel in each case.

Here's a simple example. An unmarried young man, Joe, is feeling lonely. He gets the idea to join a dance club, in the hope of meeting some single young women. He feels a bit awkward to just go to a dance club without lessons, so he'll start with lessons at the club for about 3 months. He finds two clubs, each of which teaches the styles of dancing that are popular in his community. He has spare time he is willing to devote to one of them over the next 6 months. Here's how he rates his current situation and how he imagines his satisfaction will be for each club that offers lessons:

Status Quo: Unused spare time

| Motivator | Weight | First 3 months | Next 3 months | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical: Fitness vs Atrophication | 3 | +1.00 | +1.00 | +1.00 |

| Social: Sociability vs Isolation | 3 | -1.00 | -1.00 | -1.00 |

| Social: Friendship vs Friendlessness | 5 | -2.00 | -2.00 | -2.00 |

| Artistic: Music Appreciation | 2 | +2.00 | +2.00 | +2.00 |

| Artistic: Dance | 1 | +0.00 | +0.00 | +0.00 |

| Spiritual: Confidence vs Anxiety | 3 | +1.00 | +1.00 | +1.00 |

| General Condition | -0.18 | -0.18 | -0.18 |

Alternative A: Ballroom club

| Motivator | Weight | Lessons (3 mths) | After (3 mths) | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical: Fitness vs Atrophication | 3 | +2.00 | +2.00 | +2.00 |

| Social: Sociability vs Isolation | 3 | +2.00 | +2.00 | +2.00 |

| Social: Friendship vs Friendlessness | 5 | +1.00 | -2.00 | -1.00 |

| Artistic: Music Appreciation | 2 | +2.00 | +2.00 | +2.00 |

| Artistic: Dance | 1 | +4.00 | +4.00 | +4.00 |

| Spiritual: Confidence vs Anxiety | 3 | -1.00 | +2.00 | +1.00 |

| General Condition | +1.29 | +0.94 | +0.94 |

Alternative C: University Dance club

| Motivator | Weight | Lessons (3 mths) | After (3 mths) | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical: Fitness vs Atrophication | 3 | +2.00 | +2.00 | +2.00 |

| Social: Sociability vs Isolation | 3 | +2.00 | +2.00 | +2.00 |

| Social: Friendship vs Friendlessness | 5 | +2.00 | +4.00 | +3.00 |

| Artistic: Music Appreciation | 2 | +2.00 | +2.00 | +2.00 |

| Artistic: Dance | 1 | +2.00 | +2.00 | +2.00 |

| Spiritual: Confidence vs Anxiety | 3 | -1.00 | +2.00 | +1.00 |

| General Condition | +1.47 | +3.65 | +3.18 |

The motivators above are not a complete list, but they are the ones that Joe identified as being relevant to this choice. All the rest of his motivators would be unaffected. (He could include them if he wished, but it wouldn't make any difference to this particular decision.)

Before comparing alternatives, Joe assigned a weight to each of the motivators, according to how important they are to him. As you can see, he set friendship as five times more important than dance, which he doesn't care about much. For those of average importance to him, he set the weight to 3.

Next he set the status quo "traffic lights" according to how he feels, which isn't going to change over time in the status quo alternative. For each t-light, he wrote its score beside it.

For the status quo, he calculated the weighted average for each column. To do that, he multiplied each score by its weight, added them up, and then divided that by the total of the weights. He then filled in the t-light symbol that is closest to the score. (For the "status quo", that's a "yellow" condition.)

Finally, he calculated the overall average across the whole 6 months. Because the first three months and the second three months had exactly the same duration, all he needed to do is calculate the average of those two results. That result is in the lower-right corner of the table.

He did the same thing for each of the two alternatives, according to how he anticipated they would turn out.

Now he can compare overall satisfaction of every option.

As a different way of doing this, Joe also considered adding up the satisfactions rather than calculating an average. However, he realized there could be a problem doing it that way. The motivations to be satisfied could be classified in a more granular way, in which case there would be more of them to be tallied. Or he might use a less granular approach and simply make 3 ratings for "physical, social, and artistic" satisfaction.

If different people were to assess Joe's situation, to calculate a total satisfaction, they might each come up with different totals depending on whether they use broad or granular ways of defining the motivators. But if they calculate an average, they will all come up with similar ratings. Moreover, the average will fall within the range of the t-light values, so it's easy to judge what level of satisfaction it falls into.

The first alternative is a well-established dance club with excellent instruction. The second alternative doesn't have such excellent lessons, but most of the people who go to that club are single, while the first club is attended mostly by married couples.

In either case there is a membership fee, but the price is pretty close for each club, and he can easily afford either one. He contemplated buying memberships in both of them, but he prefers to not spend so much on this experiment.

He predicts he would have some anxiety about taking the dance lessons, but he would overcome it by the end of the 3-months of lessons. After the lessons, he would continue for another 3 months, just to enjoy it and to pursue friendship with the single women he might meet.

Overall it appears that Alternative C is best, because it has the highest score. He isn't sure what are the odds that this is going to achieve the results he expects, but if he knew that, he could multiply the score by the odds. He is fairly confident, so he chooses Alternative C.

Note that the above process is very similar to what a corporation would do when acquiring an expensive product, such as factory equipment or a complex computer system. All of the desired features would be identified, weighted, and then prospective products would be scored. The difference here is that it is a personal decision meant to produce happiness, so we are rating the options against motivators rather than product features.

Would a person actually go to this trouble to evaluate the alternatives? Perhaps not, but he would do well to at least consider what alternatives there are, what advantages and disadvantages there are for each of them, and what kind of satisfaction he might get from them. Then as he imagines the results, a preferred choice might emerge in his mind.

Here's something else to think about: If Joe liked dancing more than his "+1" weight on it implies, it would be a lower risk experiment, because in the lack of finding friends he could at least get plenty of satisfaction from the dancing itself. Possibly there could be other things Joe could do to meet people that he would enjoy more. Formally rating alternatives is not a substitute for creativity and investigating of possibilities!

This example is just a slice of Joe's life. For a happy life, he plans activities that provide satisfaction over time across all his motivators.

All of Joe's judgements of satisfaction are approximations, because it's very hard to know exactly how satisfied he will be. Part of the problem is that his mind doesn't yield precise results.

As a simple example of this mental limitation, present someone with a glass of water. Ask them to stick their finger into it and tell you what is its temperature. Probably the best they can do is to rate it as one of: very cold, cold, lukewarm, warm, hot, or very hot.

Nevertheless, if you then give someone a second glass of water with a slightly different temperature from the first one, the person can tell you which of the two is warmer.

Going back to our previous dance club situation, suppose Joe wanted to asses which club has the better music. If the two clubs were each using pre-recorded music, he could get the playlist for the classes, and listen to the music himself. By direct comparison he would know which he likes better.

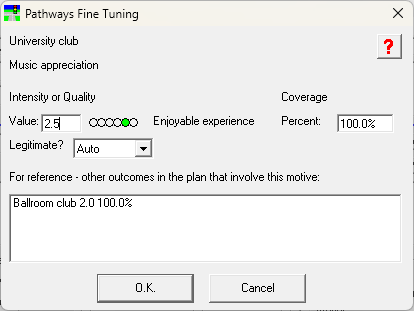

When the difference is slight, it doesn't make sense to be restricted to "T-light" scoring of integer numbers. He could pick something in between, like this:

The above example is from a software package that lets you score alternatives as we have illustrated in our dancing story. The user put the score part way between t-light standard choices:

| Range | Symbol | Standard Value |

|---|---|---|

| >= -5 and < -3 | Double-Red | -4 |

| < -1.5 and >= -3 | Red | -2 |

| < 0 and >= -1.5 | Yellow | -1 |

| >= 0 and <= 1.5 | Blue | +1 |

| > 1.5 and <= 3 | Green | +2 |

| > 3 and <= 5 | Double Green | +4 |

In the dancing story, this slight difference in music quality would not have made any difference to the choice being made. But if the two alternatives had been very close, this might have been the tie breaker.

For simple decisions that only affect one motivator, and where the difference between alternatives is slight, a side-by-side comparison is an effective way to choose.

Suppose you are going grocery shopping, for example, and your shopping list includes some canned stew. There are two brands on the shelf. How will you know which one you will like best? One way to find out, is to buy one of each; then cook them both at home and taste them.

And in fact, in daily life, it is typical to conduct little experiments like that. For example, a person might buy the same groceries that they usually get, but occasionally add some new different foods to the cart to try them out. They may also vary the amount they buy if they find that they didn't buy enough.

Similar "fine tuning" can be done for recreational activities, education, and other things, varying not only the choice but the amount of time applied to them.

In other words, the person avoids "over-planning" what they will buy. They may plan ahead enough to earn money to buy food, and they may plan to buy groceries, and they may even keep an inventory at home of foods they regularly eat. But they will not pre-define the content of their shopping cart weeks or months in advance.

One must also keep in mind also that the need can vary. A person's desire for food can change if they undertake a lot of exercise, for example. This can also be true of other motivators. So if a person plans ahead, they need to allow for some flexibility.

Another approach to judging a satisfaction that is hard to estimate, is to use an alternate measure. In the case of food, we know that the body evaluates food based on its energy content (detected by sweetness), as well as its taste and smell. So, one could provide alternate measures, for example, by testing the energy content of food and measuring it accurately according to calorie or kilojoule ratings.

With some experimentation one could determine how much energy content is necessary to sustain a given person with their typical weekly activities. One could also measure things that the human body doesn't detect very well, such as nutrition. This would enable a much more useful assessment.

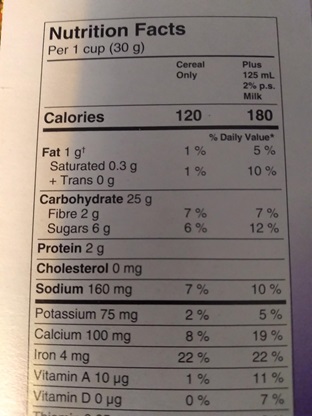

Most packaged foods have nutrition labels, as in this example from a breakfast cereal:

In conjunction with the ratings of the foods, you would determine

what your body's energy and nutrition needs are. For example, you

can look up calorie needs according to your height and weight using

available charts or calculators, such as this one:

Mayo clinic calorie calculator.

The idea would be to use data to determine which foods are not just tasty to your senses, but also fit in a healthy (green rating) or very healthy (double-green rating) category according to your needs.

This method can be useful when you are planning for someone else, and you don't have feedback from the person of whether they find the food to be adequate, or if you don't trust them to tell you the truth. It may also reveal something to yourself that your own senses didn't notice. For example, many packaged foods have a lot of sodium, and you might discover that you are consuming too much of that mineral. This is something you may not realize just by tasting it.

You can also use this data-driven approach to evaluate other satisfactions, such as maintaining physical health via exercise, adequacy of sleep (eg: wear a smartwatch that monitors your sleep duration and quality), etc.

Of course, some satisfiers are harder to measure that way, for things such as friendship and love, but even for those there are some tools to help with assessment. An example is the assessment questionnaire on this web site for evaluating a potential partner for marriage.

Available tools don't necessarily use the "traffic light" style indicators, but typical ratings such as "awful, bad, neutral, fair, good, or very good" are basically the same thing, and likewise you can translate scored tests to the same kinds of ratings.

In the dance club example, we evaluated each option, rated the satisfactions each would produce, tallied them, and finally we produced a weighted average. We then picked the one with the highest score. However, there is a certain situation when this method doesn't actually produce the best choice: the disaster condition!

This situation was explained as "the car gauges analogy" within the topic, Pursuing Happiness. The condition of a running automobile was judged by examining the various gauges, such as battery voltage, water temperature, etc. As most of them were within the manufacturer-recommended range, the average condition of the engine was good. BUT, one gauge was low: oil pressure. An internal combustion engine without oil is soon wrecked, and that's what happened!

Humans are like that too. If a person is starving, it doesn't matter how much friendship, music appreciation, good sleep, or other pleasures he enjoys, he cannot survive. Likewise, severe loneliness, extreme guilt in place of peace of mind, or other "double red" conditions can be critical. People with those conditions sometimes choose suicide.

When a person is in extreme pain, it is like alarm bells going off in their mind. It distracts them from everything else they might want to do, so it becomes really difficult to enjoy anything. Consequently, one double-red for a person can outweigh all the greens and double-green satisfactions in that period of time. To illustrate, here's what just one very miserable hunger does across the motivators:

This becomes very important when we get to the topic of judging wellbeing across a population. Wellbeing can be improved by having such things as a shared educational system, shared health care, and other benefits. But these have to be paid for somehow, typically by taxes. If that tax system puts too much burden on any of the population, that can put them into a double-red condition. That would be totally unacceptable, so if it happens, it's a system that needs to be fixed.

People generally have a desire to live. This is present in the motive list as the desire for "safety vs fear." The only case where a person might prefer death is due to extreme suffering with no hope for it to end, which is a fate worse than death.

However, suppose we are considering two alternatives, one of which has a person living their full lifespan, and the second of which has the person dying young. Let us further suppose that this is being planned on behalf of the person, and it is not revealed to him that one alternative would have him die young. Therefore, he would have no fear as he pursued either of these alternatives.

We can arrange this scenario so that the two alternatives yield the same average satisfaction. That's achieved by having the same level of satisfaction in each year in which he lives, in each alternative. For the early death alternative, only the living years are scored, and the years of life he loses in this alternative are not scored. So, the average satisfaction would not be affected by his death! The two alternatives would seem to yield the same satisfaction!

Obviously he would not agree that this method of scoring truly represents what he wants. He is not indifferent to an early death!

One way to correct this is to score an "opportunity cost" for each year in which his life is shortened. Whatever his average yearly satisfaction is just prior to his death, assume that is the kind of life he will be missing out on. So take that, negate it, and then make that the yearly opportunity cost for his lost years! Now the alternative in which he dies young has a very unfavorable score!

Here's what the total satisfactions might look like for Joe over the next 55 years (assuming that Joe is about 20, and that he will live for 55 years in a normal lifespan):

Joe Alternative A (Healthy life)

| Early Career 5 years |

Raise family 25 years |

Retirement 20 years |

Last Years 5 years |

|---|---|---|---|

|

+2.0 |

+3.2 |

+3.5 |

+1.3 |

Joe Alternative B (Joe smokes tobacco)

| Early Career 5 years |

Raise family 25 years |

Early Death 25 lost years |

|---|---|---|

|

+2.0 |

+3.2 |

-3.2 |

For alternative A, an overall score is:

((5 x 2) + (25 x 3.2) + (20 x 3.5) + (5 x 1.3)) / 55

= (10 + 80 + 70 + 6.5) / 55

= 3.03

For alternative B, an overall score is:

((5 x 2) + (25 x 3.2) + (25 x -3.2)) / 55

= (10 + 80 - 80) / 55

= 0.18

By this calculation, the "healthy life" alternative is preferred.

There is one more thing to notice about this, which is that the "blue" condition in the final years of Joe's life. In his final years, Joe expects he won't be able to enjoy sports and other activities as much, because he will likely have some limitations, such as a need to walk with a cane or walker. So he will still get satisfaction from life, but not as much as before.

This lower satisfaction will lower his average overall, because the earlier years had higher "green" level satisfaction. Nevertheless, it makes senses to continue living so long as Joe is getting some satisfaction from life. The reason for this is that past conditions are irrelevant to choices for the future. By the time he reaches the final years of life, all the first columns of the chart will be past conditions.

This is a well-known principle that is used in economics and business administration. There, it is described in money terms, which is that "sunk costs are irrelevant to an investment decision." For example, suppose a business has a factory that is losing money, but for a small investment they could make it more efficient. After the investment, they could earn money from it that would pay off that investment and earn a profit as well. It doesn't matter how much money they lost on the factory to that point it time; it makes sense to make the investment regardless. This is true even if they will never recover the full cost of the factory.

Likewise for Joe, it doesn't matter how satisfying or unsatisfying his past life may have been. He can't change the past. For his decisions, what matters is the future. And, because he doesn't want an early death, it makes sense to avoid it.

It is important to treat an early death as an undesirable outcome, especially as we get into our next topic, of rating the success of a group of people. Groups sometimes undertake wars, and typically the lives of people are treated as unimportant to the goals of the war; that is a big mistake that we don't want to make!

Next chapter |

What do you think of the content on this web page?

| Site Search | |

Return to Universal Ethics home page |